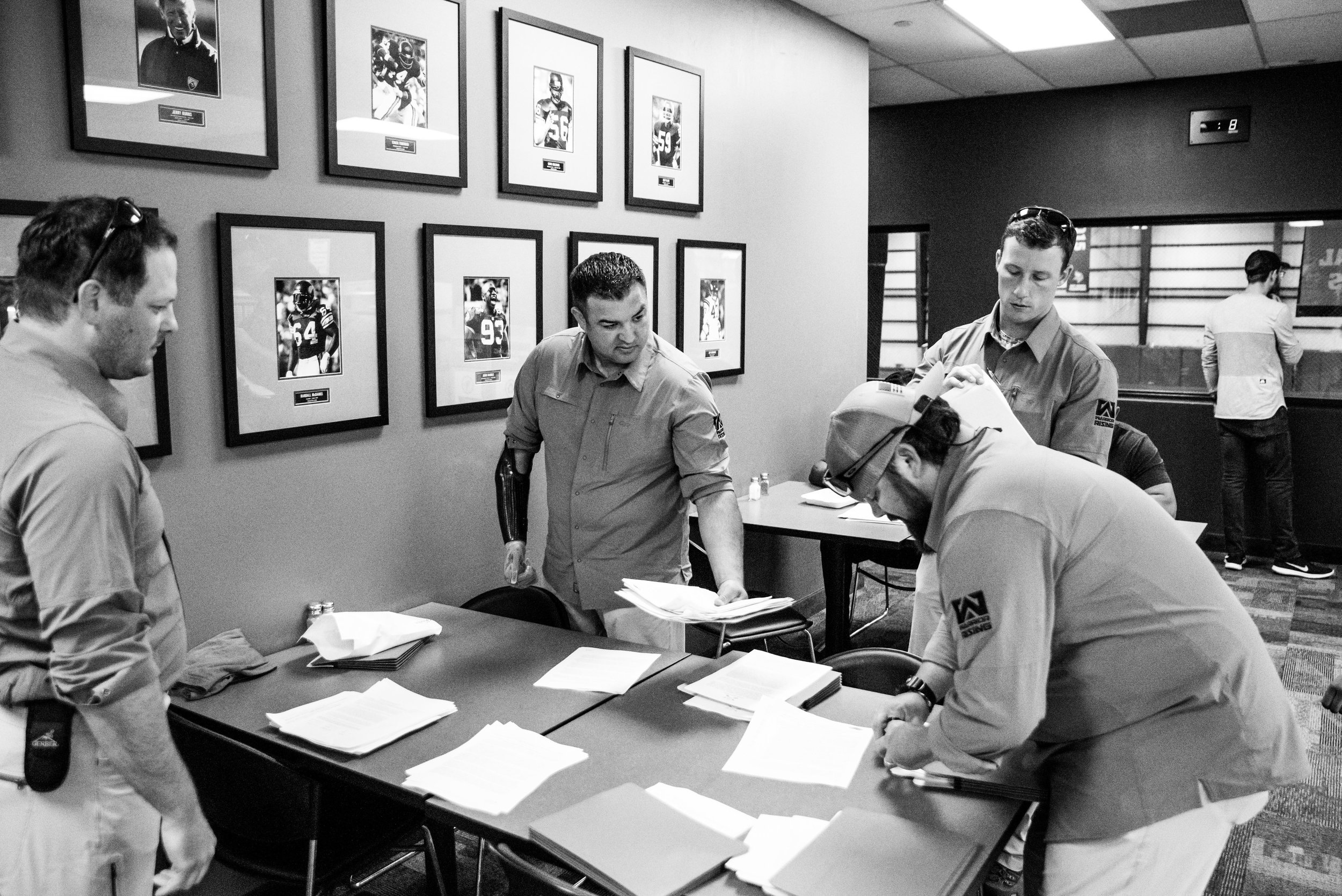

SSG Kyle Daniels (Army Special Operations, OIF Veteran) - The Veterans Project

“ ‘The green beret’ is again becoming a symbol of excellence, a badge of courage, a mark of distinction in the fight for freedom. I know the United States Army will live up to its reputation for imagination, resourcefulness, and spirit as we meet this challenge.”

— President John F. Kennedy

Humility. This word is used often as the common quotient and summation of a successful legacy within the military. There is pride in remaining humble which may sound like an oxymoron but those who have served understand. This rings even more true for Special Operations brethren. The greatest endowment one can leave the teams is a memoir of humility and a sacrificial attitude. Lately, some have said that things are changing in the world of Special Operations and that some of that humility is lacking. There won’t be much said in this blog about that, because the most successful men detailed in this project have been the most humble. Kyle Daniels is no exception to that rule. His down-to-earth demeanor and sense of humor immediately make you want to know him better in every facet of his life. His ability to turn any situation into a matter of laughter is a quality that lends itself well to the high-stress, intense pace of a Special Operations lifestyle.

The old saying, “laughing is better than crying” can apply in a lot of those combat situations and Kyle is a master of that mantra. Still, more impressive, is Daniels’ ability to listen and learn from every single situation life presents. He’s constantly seeking mentorship in every facet of his life and that’s what made him such a highly-regarded teammate and soldier. These qualities are what make Kyle the perfect example of a Green Beret, and those same qualities lend them to his successes as an athlete, mentor, corporate employee, and vetrepreneur. The intensely high standards of service set by the Special Forces cadre certainly honed these skills, as Daniels is a living embodiment of selfless service and the Green Beret motto, “De Opresso Liber (To Free the Oppressed).” Still, in this interview, you’re going to hear from a man that admittingly made mistakes throughout his life and is thankful for the lessons learned in those experiences. That portion of Kyle's foundational characteristics play part-in-parcel with his always humble attitude. Here's SSG Daniels.

Talk to me about how you were raised growing up and what the young Kyle Daniels was like.

KD: I had a pretty normal, Midwest upbringing in Southern Illinois. We were a typical middle-class family and I remember my father, in particular, being a major influence in my life. He was always big on leading from the front and by example. I know it’s pretty cliche and I’m sure you hear it a lot but my father was the hardest worker I’ve ever met. He was always the cornerstone of our family, especially me. I can attribute any success I had in any leadership role to my father and how he raised me. His leadership model was that of a selfless servant, always looking to help others. He was big on working until the job was done and always doing more than what was expected. Our mom was pretty hard on us as kids. Although we didn’t really like it at the time, her methods and intentions were for the best. She didn’t let us run around and act like assholes all the time (laughs). She knew exactly what she was doing of course. A lot of the Q-Course was doing not only what was expected but going above and beyond what was asked. You needed to exceed expectations and my mom instilled that in me growing up. As kids, we were purposely pushed to do a lot of things we didn’t understand at the time, but looking back the reasoning behind it all is clear and definitely set me up for success later in life.

Why’d you join the Army in the first place?

KD: The first thing that got me interested in the Army was my dad being in the Army. We don’t have a big military legacy in our family, but my father’s service definitely inspired me. I always thought my dad was superman, but when I found out he was in the Army, that really got me excited. I remember graduating highschool and I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. I thought I was going to get a full ride scholarship to play football and that obviously didn’t happen (laughs). My parents really wanted me to go to college but that wasn’t really my desire. I went to the local college really just to oblige them. I was halfway through my first semester and I realized I was spending more time in a pool hall than class. I thought to myself, “I can’t keep wasting my dad’s money like this so I probably should follow what I really want to do.” It was also 2003 so things were pretty heavy overseas at the time and I was an able-bodied male so I knew I should probably join up.

I thought to myself, “What better time than now?” I remember getting up in the middle of my Conceptual Physics class and going straight to the recruiter (laughs). When I got home that day my mom and dad asked me how school was and I was like, “Well, I joined the Army (laughs).” They thought I was joking around completely. I showed them the paper and you could’ve heard a pin drop. My dad had kind of a rough upbringing and his goal was to provide a better life for his family than he had. He felt like I could be doing something other than fighting overseas and should be taking advantage of the opportunities he provided for me. Honestly, I think that was any parent’s reservation at that time with two wars just starting. Who wants their kid to go to war? My parents asked me what I signed up for in the Army. I told them I signed up for the 18-Xray program and was trying out for the Green Berets. There was more silence. I feel like silence and disbelief was the theme of that conversation (laughs). I remember my dad randomly started asking me questions that might be on the ASVAB. I think that was his way accepting my choice and showing support. Initially, I thought he was mad, but looking back I could tell he genuinely cared and wanted the best for me. It was his way of saying, “I’m going to set you up for success whether you like it or not (laughs).”

What do you remember about getting into the Army, going through Basic Training, then on to the Q Course?

KD: Basic Training was very easy for me physically and I think a lot of the bullshit that some of the younger guys struggled with like cleaning, attention to detail, or any of those little things was not that big of a deal to me. As a kid, I had to clean the bathroom, make my bed, or sweep the kitchen before I got to go play with my friends. So, when I got to Basic Training I didn’t struggle with all those seemingly petty things. I thought my parents were making me work excessively as a kid, but once I got to BCT it made things so much easier. When I began the Q-Course I was in good shape, which made all of the physically demanding challenges relatively easier. Attention to detail is heavily stressed in the Q-Course. Luckily my parents ingrained in me a very sharp focus on attention to detail, so those things came natural to me. Plus, I was so goal-oriented that I was going to do absolutely everything in my power to don the Green Beret and get that long tab on my shoulder. I didn’t care if I had to low-crawl through the gig-pits every night at midnight… I was going to make it happen.

Can you talk about the process of becoming a Special Operations soldier?

KD: There was so much talk and speculation before the Q-Course even started. You’d hear guys saying stuff like, “I heard they’re going to break all our fingers and send us into the woods naked (laughs), and whoever gets out alive makes it.” That’s not even remotely close to what happened of course (laughs), but those were the types of thoughts that the ‘unknown’ stirred up inside of us; the stress started before the course did. It was definitely very hard physically. Doing land navigation in the middle of the night without any help from a lighting source was a big obstacle to overcome. I didn’t grow up hunting, living in the woods, or anything like that so that was tough for me. I went through SOPC first which stands for Special Operations Preparation and Conditioning, which in my opinion was physically harder than SFAS (Special Forces Assessment and Selection). They definitely picked the right cadre for SOPC. Every instructor was an absolute beast physically and mentally. Most of them were the initial team guys that went into Afghanistan and/or Iraq. These guys took their job very serious because they knew exactly what we would be in for down range. The harder they could make it on us in training, the better we would fare in combat.

What was the actual Selection process like?

KD: Selection was a major learning curve but I think my upbringing set me up for success. My dad instilled a lot of things in me like, put your head down, get to work, and help others along the way whenever possible. So that was the attitude I brought to Selection, which goes hand-in-hand with the psyche a team guy should have--a team player who gets shit done. There are a lot of individual events in Selection, but the overarching theme is “team” and team-based events. That’s where the cadre are able to make an assessment of how well you are able to work with and lead others in highly stressful situations. It was a very grueling month physically and mentally, but I wouldn’t want it any other way. It’s comforting to know that the guys on your left and right on a team were able to embrace the suck and persevere through the same hardships that you went through, and anyone who couldn’t hack it didn’t (hopefully) make it to a team.

What do you remember about some of the unique challenges of the course?

KD: A lot of time being cold and wet (laughs), especially during the Small Unit Tactics phase. You’re constantly in the field, cold, wet, mentally and physically exhausted. You have to find this extra layer of yourself to make it through those challenges. Everyone is going through “the suck” and a lot of people quit. But the ones that make it through develop an extra gear they can tap into when the are faced with challenges in the future. I had to block out the short-term discomfort and keep my long-term goals in the forefront of my mind. I wanted that Green Beret so damn bad, and I told myself every day I would do whatever it took no matter how badly it sucked. Whether it was a 15-mile road march with 60-90 lbs on my back, or lying in the prone position in a patrol base at 3:00am in 20 degree weather and watching the dew crystallize. These types of things created the mental struggle. We’d get a task and it was up to us to find it within ourselves to push past those barriers and meet our objective. A lot of the guys that didn’t make it let the moment get the best of them. The repeated testing of your mental composure is a big part of what creates a good Special Forces soldier. That testing fortifies the attributes you need to be a war-fighter at the highest level.

What was it like when you got to the teams?

KD: I was assigned to 10th Special Forces Group when I graduated the Q-Course, and my team was already deployed when I arrived. All of us new Q-Course grads did a month of pre-mission training before we shipped out. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t have some nerves going into that first deployment. I remember thinking, “Damn, as soon as I step off that tail ramp it’s going to be guns blazing.” It wasn’t like that at all though (laughs). We were all a bunch of hard-charging young Green Berets that had this mindset of kick ass and take names. We were preparing our mind to do work and knock Al-Qaeda off one by one (laughs). Everything was very professional and we were treated like adults. There was no hazing or treating the young guys like they hadn’t earned their place.

I actually met my team overseas. We landed in the middle of the night and the first person from my unit I met was SGM Socia. Everyone was like, “Get ready to meet Frank the Tank.” I was thinking, “Great… (laughs).” He sounded intimidating but he was actually a really cool guy and was quite personable. My team sergeant picked up me and the other new guy assigned to the team and we headed to the team house, which turned out to be a small guest house inside one of Sadaam’s old palace complexes. We got a couple of hours of sleep and then met the rest of the team early the next day. My senior was definitely very brash and very old school in his welcoming style (laughs), but it wasn’t anything I didn’t expect. The guys on the team were solid. Everyone took me under their wing and showed me what being on the team was really all about.

What was that first tour of Iraq like?

KD: Our team’s primary mission was FID (Foreign Internal Defense). We were in charge of running the Iraqi Special Warfare Center and School (ISWCS). My team and I were the cadre for training the Iraqi Special Forces and putting their current and new soldiers through the Iraqi Special Forces pipeline. The goal of this mission was to train a fighting force capable of conducting some of Iraq’s most sensitive missions, and to train their trainers so they could take the mission over so we wouldn’t be there forever. It was an equally fun and frustrating mission at times working side by side with the guys we trained, but there were a lot of times I wish we just did kinetic operations with team guys. That rarely happened anymore at that stage of the war. Getting the majority of them to hit a standard silhouette target proved difficult at times. So in the back of my mind I was thinking, “Get them to a standard where they won’t get any of my brothers killed.” I initially thought we could train them to our standard, but that idea was snuffed out after about a day of working with them (laughs). The FID mission is very important in our line of work. It’s challenging, at times, to learn all of the nuances of working with local nationals, and there are so many different cultural barriers that have to be overcome. But it’s one of the most important jobs within the counterinsurgency strategy.

Talk about the deployment.

KD: The first two months were mostly training the ISF soldiers. I wanted to be fast-roping out of helicopters and kicking down doors because that’s what I’d signed up to do. I saw a lot of guys on other teams doing the direct action missions and I wanted to be a part of that. About halfway through the deployment I was finally able to straphang with one of our sister teams and leave the wire. My very first mission we were dispatched to Baqubah. This was when every SF team in the area was hunting down Zarqawi. All of our intel suggested that he had this huge militia reinforcing his compound and we could expect to make contact as soon as we arrived on target. I was the M240 gunner in the rear of an open-back humvee. I remember as soon as we rolled up on target hearing the crack of an AK-47 round whip pass my head. It remains one of the most indelible moments of my life. I’ll never forget that first round fired at me… the sound, the feeling in my body. It was loud enough to make my Peltors cut off the sound and close enough to feel the air break as it flew past me. We didn’t Zarqawi that night but we did get into it.

I remember thinking, “Oh shit, it’s for real now.” Someone was legitimately trying to kill me and that’s a strange feeling. The TC was the Team Sergeant for 6/5. He yelled, “Daniels why are you just standing there? Return fire! (laughs)” He started pointing his laser where the ground elements were in contact. I didn’t freeze for long but it’s embarrassing to admit I froze for a split-second to the point where someone yelled to return fire (laughs). After that initial shock and verbal kick in the ass, my training kicked in and I started to lay down fire. When I got back to base, I had a moment of contemplation where I thought to myself, “A bullet just came close enough to my head that I felt the windbreak. If our truck had parked a few feet to the right I wouldn’t be here anymore.” Those kinds of thoughts will mess with your mind if you dwell on them. All of the build up in my head about my first combat operation didn’t do the actual experience justice. You can think about and prep for combat as much as possible but you truly won’t know your response until you get into it. It’s the most unique experience in the world.

Can you talk about one time in particular where you were nervous about the situation?

KD: After the stint in Baqubah, I was able to straphang on a few of the missions conducted in Sadr City. Sadr was one of the most dangerous places in Iraq at the time. Even though we went in armed to the teeth with manpower, guns, and close-air support, those operations always seemed more intense. Going into Sadr made the hairs on your neck stand up a little firmer compared to other places. The fighters in Sadr, known as the Mahdi Militia, were battle hardened combatants and were no strangers to a gunfight. It was pretty much a given that we were gonna get it on when we got on target, if not beforehand. They were definitely a cut above the average spray-and-pray radicals and warranted every bit of respect a worthy foe is entitled. Even the mention of the words “Sadr City” in an Ops room would garner all of the attention towards that conversation. It was one of those places that had this dark stigma attached to it.

We were always after HVTs (High-Value Targets) and Sadr was a cesspool crawling with a lot of the ones we were targeting. We always had an AC-130 Spectre Gunship above us on those missions. As comforting as that was, if you had to call-for-fire shit was starting to hit the fan. However, seeing that thing go to work through NODs had to be one of the coolest things I’ve ever seen. I felt like I was watching something out of Star Wars. I remember thinking to myself, “Why in the hell would anyone ever want to fight us? (laughs).” Somehow through all of our engagements (the ones I was a part of) we didn’t suffer any American casualties, and had very few ISF/ICTF injuries. I couldn’t be more thankful that was the case, however, in a way it kind of instilled a false sense of confidence in me. I didn’t care where we went… I always thought, “We’re going to win every time. Who’s going to beat us?” That might sound cocky but that’s how I felt.

What was your second tour like?

KD: The second deployment was different. We were off the beaten path and we didn’t have the same strength in numbers. We were in a small village in Northern Iraq called Qayyarah and had very few reinforcements. We were re-standing up an old team house that hadn’t been occupied in about two years. Some of the stuff we were dealing with was ridiculous. We had a hodgepodge of regular Iraqi Army soldiers and minimal time to get them trained and operational. I only trusted a handful of those guys and was leary about the remaining majority. The lack of trust made that tour a lot harder. A lot of these guys would get issued training ammunition and they’d show up to training without any ammo; they stole and sold it. I remember one mission we did our pre-combat checks--making sure they had enough ammo, flashbangs, batteries, etc.-- and routinely found guys without ammunition in their magazines or their weapon! One of the guys had flashbang shells without actual flashbangs inside. It was like herding cats and pushing rope. They were selling this stuff to God knows who...most likely our enemies we were targeting that night (laughs). It’s hard to trust guys like that. Mediocrity would have been high praise for this new batch of IA.

On this deployment our ratio of Americans to Iraqis was something like 1:10, with only about 10 or so Americans on the ground on a given night. Those ratios with guys you can’t fully trust is nerve wracking. Our marching orders were what they were, though, and when you’re a Special Operations soldier you don’t say, “That’s too difficult.” We’re the best of the best so it was our job to make shit happen. I learned some of my greatest lessons as a Green Beret on that tour because I truly had to take ownership of every situation. Any successful team guy I’ve met had an ownership mindset and a “make shit happen” attitude. A lack of resources simply meant learning to be more resourceful. Later in that deployment, a small contingent of our team moved from Qayyarah to an even smaller outpost further in the boonies to meet with a different IA unit. They were equally incompetent and that was another shit show from the very beginning.

What was the toughest thing about that tour?

KD: It was definitely the night we got hit by an IED. Prior to that incident, we conducted a relatively stress-free, successful operation. We caught a corrupt Iraqi parliament member and a few mid-level AQI financiers. It was this big dinner party and we were pretty stoked about catching them all at once. Our IA guys were relatively easy to handle that night, too. There were no friendly fire incidents with them so that was a win for us (laughs). The old saying is, “Complacency kills.” On the ride back to base that night I was guilty of letting complacency set in. I was in the 3rd truck back and remember losing my focus on my immediate environment when all of a sudden I heard a loud “boom” and saw a huge cloud of dust. I was like, “What the fuck was that?” The two vehicles in front of me basically disappeared and we swerved to the left and avoided the crater. The crater was probably the size of a living room. I don’t know what exactly happened but by the grace of God, the IED must’ve been buried too deep or something.

That IED was catastrophically large but the worst injuries were shrapnel wounds. Time seemed to move in slow-motion in that moment. We had an air scan plane above us and they were able to track down the guys who’d hit us. It was remote-detonated and air scan saw the guys squirting off target. A small element of us who weren’t in the first two trucks hastily assembled a small assault element and maneuvered towards the squirters. We were trudging through this cow pasture and got about 30 meters away from where air scan was IR lighting the enemy location. They were hiding in an area of tall reeds and we couldn’t pin their exact location. One of our elements maneuvered to flank. Before they swept across our objective I paused all elements and yelled out, “Frag out!” I pulled the pin and right as I was about to throw the grenade I slipped in some cowshit (laughs) and the grenade went about 10 feet to the left of where I meant it to land. Our flanking element swept straight across and then we moved in and closed the gap. We ended up catching this dad and his son who’d been the ones that detonated the IED. That night was sketchy because a good buddy of mine, Adrien Elizalde, had been killed by an IED about a month previous. So, that was still very much in my head.

Do you ever question any of the decisions made or choices you made over there?

KD: It’s still such an ego hit for me… One of the worst things a soldier can go through is a friendly fire incident, especially when you are in a leadership role. Fortunately, this incident did not involve any US troops, although that doesn’t decrease the severity of what happened. It happened with our Iraqi counterparts. I was one of the assault team leaders that night and these were the Iraqis I was directly responsible for training and leading in combat. Regardless of how combat-ready they were or were not, we had to run ops with these guys. I did everything in my power to train them right. One night, we were hitting multiple targets and somewhere there was a communication breakdown.

We had two rogue Iraqi fire teams enter the same building from opposite sides and one of their guys got killed, another was injured. It’s something I take complete ownership of. I still think about what if it had been one of my teammates? None of my brothers got hurt that night but it was still tragic to lose one of our counterparts. It was a hard pill for me to swallow. Sometimes I still think about things I could have gone differently. Was there a shortfall in the training? Could I have briefed them better? Should I have stressed communication more than shooting at their level? It’s still hard to live with at times. It would have been easy to chalk it up to “the fog of war” but I wasn’t about to pass the buck like that. As a leader, I had to own the situation and own the corrective action to ensure that never happened again, or at least was mitigated as much as possible in the future.

What was the hardest thing about that second deployment?

KD: One of the toughest things about that second deployment was coming to terms with the fact that these IA soldiers weren’t as motivated to fight for their own country as we were. How do you motivate someone who has no national pride? They weren’t willing to fight the people who were oppressing them and their families and stripping away their freedoms. I have a hard time reconciling that in my head. It’s such a weird thing to me because freedom is precious and needs to be vigilantly defended or it will be lost. How can you watch some other nation come in and watch its people willingly put their lives on the line while you just passively standby? I don’t understand the lack of pride. Of course, I’m painting with a broad brush when I say that, but that seemed to be the status quo with this group. Our op tempo was so high that we were running missions almost every night and training these guys during the day. How do you get guys who aren’t even motivated to protect their own country to go out on a nightly basis and not revolt?

Speaking on the psychology of taking lives, what was running through your head when you pulled the trigger?

KD: In the moment, there isn’t too much thought about taking lives. Our training was so effective in that the violence of action became second nature when provoked. You don’t have to consciously think about the action of pulling the trigger when the time comes. It was actually really cool to feel my instincts turn on in those moments where I was required to be combative. There’s always the thought when you’re shooting paper targets or silhouettes, “What’s going to happen when there’s another living, breathing soul on the other side of my weapon? Am I going to freeze? Is my conscience going to stop me?” Without sounding too casual, it was actually a very easy action for me.

I never struggled with bad guys dying and there was never a single negative thought about that. I almost wondered if there was something wrong with me because it was so easy to pull the trigger at times. I thought, “Am I a sociopath?” Don’t worry, I’m not (laughs). In my opinion, the training was just that thorough and I never questioned my actions. Anytime there was a gunfight it was because we were engaged first. We weren’t out there just stacking bodies for the hell of it (laughs). There was a rhyme and reason and our contact was always provoked. The training held up in the most stressful situations I was in. There’s nothing more stressful than combat. I mean when you look at the spectrum of stressors in this world, there’s nothing more stressful than life and death situations. I just had it in my mind that I knew I was doing good for my country and doing good for the people in that area, so taking lives was justified in those situations. There was never a doubt in my mind that I wasn’t doing the right thing.

What was getting out of the Army like for you and when did you realize you were done with the military?

KD: After that second deployment (2007), my company was tasked with the CIF mission in Germany. I got back from that trip and the combat deployment cycle was different. 2006-07 was the peak of the war in Iraq and I heard a lot of the older guys talk about the combat life cycle. The guys from the Clinton-era talked about the inevitable changes that would happen as combat operations slowed. Things overseas were on a steady decline and the ROE got tighter and tighter by the day. It seemed like every progressive OIF had more restrictions attached to the way we did business and that makes it almost impossible to win the war. War is a terrible thing, and restricting the fighting forces and making things politically correct just doesn’t work. I also wanted to shift my focus towards a different Special Operations skillset.

I got more into the Human Intelligence side of things at that point so I went to a different unit for the rest of my enlistment. On a more personal note, I thought about how EZ and all my fellow SF brethren paid the ultimate sacrifice, which in turn made me think about my other life aspirations. I felt, and still do, like I owed it to all of them to live my life to the fullest without regrets. I fulfilled one of my childhood dreams of becoming a Special Operations soldier so I wanted to shift my focus and pursue my other dream of playing golf professionally. I didn’t want my military career to be the pinnacle of my existence and I wanted to try something different and live a diverse, strong life. So at that point, I made up my mind that I was going to transition out of the Army and focus on my other dreams and aspirations.

Humor is obviously a big thing with you. Do you have any funny stories from overseas?

KD: We came into the chow hall after a night full of actioning targets. We left one of our teammates with the trucks to watch our weapons and ammo. We were all super tired from conducting ops all night and just wanted to get some hot food and get back to the team house. A Specialist outside the chow hall who was in charge of making sure everyone had and cleared their weapons stopped me. He said, “Sergeant where is your weapon?” I told him, “We have a guy pulling security on them at our trucks.” He replied, “Sorry, base policy is that everyone has a weapon on them in the chow hall.” I was like, “Man, are you kidding me? We just got back from running ops all night. We’re exhausted and just want to get some food.” He kept insisting so I went back to the trucks, grabbed the Karl Gustav (laughs) and tied some 550 into a makeshift sling. I went through the whole process of pointing the Gustav into the clearing barrel (laughs) and as loud as I could yelled, “CLEAR!” This guy just looked at me and I said, “Does this qualify as a weapon?” I was feeling a little frisky (laughs).

Our team carried 1911s and in order to engage the safety you have to cock the hammer back. We carried ours hot at all times because of our direct interaction with the Iraqis all day. Another time in a chow hall, some civilian contractor was like, “Hey man, just wanted to let you know that your hammer is cocked back.” I said, “Well, yeah that’s the only way I can keep my 1911 on safe.” He replied, “Well, that doesn’t seem like a good idea to me to keep your weapon like that.” I looked at him completely serious and said, “Well, not only is my hammer cocked back...but I also have a round in the chamber (laughs).” He just took a step back and was like, “Geez, that doesn’t seem right.” I laughed and replied, “Don’t worry… everyone will be okay (laughs).”

How much did your sense of humor play into your time on the teams?

KD: Humor was hands down one of the biggest things for me on a team and it’s also just a big thing for the military in general. I’ve always had extremely thick skin and a pretty good sense of humor. You have to on the teams or they’ll eat you alive. You gotta be able to laugh at yourself and be able to dish it back. If you show any sign of weakness or that something is bothering you, that’s like blood in shark infested water (laughs). I don’t know if I was the funniest guy but I always was cracking jokes. It helped with adaptability and it was a coping mechanism for me. If you can’t laugh, you’re going to be hating your life on the teams.

If Kyle Daniels was the President of the United States what would he change about this country?

KD: I’m really tired of political correctness and hypersensitivity. One thing always comes to mind, and I’m not justifying what happened at Abu Graib, but I remember talking to one of our Iraqi interpreters who’d grown up in Iraq under Saddam's rule. He was shot in the neck in the original Gulf War, and the bullet traveled through his skull and lodged near his eye. You could actually feel the tip of the bullet. He had seen some stuff and was pretty hardcore. I remember talking with him about what happened at Abu Graib. I asked him what his opinion on the matter was. He thought America’s reaction was laughable and we overreacted big time. He spent time in one of Saddam’s jails and was physically tortured and beaten daily. He said to me, “People in America have no concept of what real torture is because they’ve only seen it in movies.

You can’t know what it truly is unless you’ve lived it or seen it in person. Yeah, those guys were embarrassed but it stopped there; they weren’t beaten and tortured.” That sentiment was echoed by all of the Iraqis I encountered. A big segment of our population is so easily offended or distraught when things don’t go their way. When did critical thinking and compromising go out of style? It’s like everyone just wants to hear their own views and opinions and if you differ from that the immediate reaction is to be offended instead of trying to understand where someone is coming from and arrive at a sensible solution. The media affects a lot of that too. I remember hearing things about the war when I got back from deployment that were spun to whatever agenda that particular news outlet had. The media impacts the way we fight wars and that’s a damn shame. So to answer your question, I would figure out how to shift people’s mindset away from being so easily offended and cultivate an environment that encourages and enables constructive debate. If that were the case, congress might actually get something done (laughs).

Can you talk about the complications of battling terrorism?

KD: War is not black and white, especially given the enemy we’re facing now. We’re fighting a deeply imbedded ideology that manifests into physical acts of violence by evil men. How do you change thousands of years of culture? I don’t know the answer to that. I do know that terrorist organizations do not want people to think freely for themselves. Independently thinking people aren’t easy to manipulate, which is one of the main tactics terrorist leaders use. I think education and stability are the two biggest things that would make lasting change. Education is one of the main things that evil men in power repress from their people. If citizens don’t know how good their lives could be they are more likely to be compliant. Combine the lack of education with a constant state of instability and you have a recipe for disaster that terrorist thrive on.

Talk about character and strength in service.

KD: You never really see a person’s true colors until you see them under duress. Life in the military is full of stressful situations that afford you the opportunity to prove yourself as a leader or prove your inability handle the pressure. To this day, the people’s opinions that I value and respect the most belong to my brothers I served with. They’re the ones who’ve seen me at my absolute best and my extreme worst; they’ve seen my true character. I always had the mindset of I’d rather die in the service of my team or my country than to live and be remembered as a coward. I put a high premium on leaving a positive legacy and a reputation that preceded me in a good way. My goal on the team was to be the best teammate I could be and to make our team better so we could dominate whatever task we were given. These feelings weren’t unique to me. I knew that the guys on my team felt the exact same way. I’ve never seen selfless service so epitomized as I did when I was on an A-Team. I feel like selfless service is one of the most important values people in the military can possess.

Talk about starting your own business and the difficulties you faced in that.

KD: Hearing a lot of “no’s” and being rejected a lot can be tough. There’s a protocol for everything in the military. If I wanted to have something built for the team, or order some new kit, there was a protocol to follow to make it happen. I just had to go through the proper channels and sooner or later the request would be filled. There were mechanisms in place to set you up for success. Starting a company from scratch in the civilian world is challenging in that nobody is obligated to help or support you. In the military, someone is usually obligated to help you. There are big differences from a competitive standpoint in the civilian world, too. Initially, I reached out to other flag manufacturers for help and/or advice, only to receive a “Great idea, good luck and thank you for your service” followed by a dial-tone (laughs). Another thing is that the only person who is on your timeline is you. For the most part, you have to make your schedule work with the people who can help you out, even if it’s an inconvenience. These challenges are good, though, because it keeps me from becoming complacent and it’s educational going through this process. I’ve learned to take those rejections in stride, adapt, and find alternative solutions.

Talk about Warrior Rising and what they’ve specifically done to help you with your business model.

KD: Warrior Rising is a big reason why I am able to do what I’m doing at the level I am doing it. They’ve paired me with a mentor who is absolutely fantastic and is a proven business leader at the top of his industry. That in itself is invaluable. I’ve never dealt with supply chain issues or reaching out to suppliers and manufacturers. My mentor has helped me with all of that and more. Warrior Rising won’t do the work for you, but they are going to make sure you are on the right path and help you along the way. They are good about not blindly throwing money at ideas. They provide a hand-up, not a handout. I would never go to the board for the such-and-such amount of dollars and expect them to give it to me without a detailed plan of attack. Even with that plan of attack, they know how to refine it and make it more efficient. When I was on a team, I had guys around me who helped ensure my success. That’s how Warrior Rising functions as a unit. If the resource is there, why wouldn’t you utilize it? They are there to help you. Use them.

If you were going to give advice to someone starting their own business, what advice would you give them?

KD: It’s very important to learn from someone who’s already been where you want to go. Find a mentor like that and model their behavior. You’ll have decades of experience at your fingertips, which can save you a lot of time and money in trial and error. Having a strong support network around you can be integral to your success as well. The way you envision your idea will likely not be the way things pan out. If things had gone the way I initially envisioned with Firebrand Flags, I would have been up and running within six months and every red-blooded, patriotic American would be proudly flying one of my flags in front of their house or business. The reality of the matter is, things will likely take a lot longer than you think. Practicing diligent patience would be my advice. There will always be obstacles to overcome and you have to persevere through those. Dealing with contingencies will likely be the norm at first. For veterans, you should use your veteran status to your advantage, but know that alone will not ensure your success. People will love that you’re a veteran but don’t expect them to go out of their way to help you solely based on that. You need to have a viable idea that solves a problem in the market.

Talk about Firebrand Flags and your concept.

KD: I started it as a positive counter-measure to the disrespect that was being shown to our flag. I chose the name Firebrand based off of the word’s definition, “a person who is passionate about a particular cause, typically inciting change and taking radical action.” I got sick to my stomach watching the American flag being burned as a means of protest. That flag means so much more to me now after seeing the sacrifice of my brothers and sisters in arms made to defend what it represents. So, instead of sitting back and griping and moaning about people burning flags I decided to take action and make a change. I knew there had to be a way to produce a flag that could defend itself when nobody was around to defend it. So, my mentor, Mike Moon, who is an absolutely incredible human being, and I collaborated to make this idea come to life. We decided to make a product that stood for positive change and was as tough as the people sworn to defend it.

Where do you want Firebrand to be in the future?

KD: I want Firebrand Flags to be the official flag company of the U.S.A. I want every home, business and government building in America to proudly fly one of our flags. I also want it to fly outside all of our embassies and forward operating bases overseas. I don’t want our flag to be used as propaganda by a radical group that gets their hands on one. If, for some reason, one of our enemies got ahold of one of our flags they would have to go to extreme lengths to destroy it, much like they do when they are face to face with an American service member.

How did your time on a Special Operations team help you now in your work with Firebrand Flags and with the civilian world overall?

KD: The two biggest things that crossover are building relationships and adapting to uncertainty. In my corporate healthcare job, I’ve found that building relationships is something that directly translates from my time on a Special Operations team. One of a Green Beret’s core tenets is to build rapport with indigenous forces so you can work closely with them to achieve a common goal. As effective as a 12 man ODA is, the only way to exponentially compound your efficacy is to form relationships within communities and villages and build a cohesive guerilla fighting force. In the corporate world that translates to building relationships with co-workers and building solid teams. When I get home from my day job, it’s my time to work on Firebrand and build that business. I have certain objectives I want to meet, but often times some sort of contingency will arise and I’ll have to adapt my approach in achieving a particular objective. That’s the same type of resilience I had to learn on the teams. When I hit those roadblocks, I simply have to adapt, overcome, and do whatever needs to be done to accomplish the mission.

Why did you specifically get into golf after the Army?

KD: Golf was the other childhood dream of mine but I never had the financial means to pursue it. We weren’t poor but we didn’t have extra money to allocate for that. When I was a kid I used to save up my extra dollars to pay for golfing equipment I’d find at garage sales or anywhere second-hand. Come 2002, 2003 the Afghanistan and Iraq wars were in full swing. I was getting out of highschool and having to make some major decisions about my future. I chose to pursue my dream of becoming a Special Operations soldier. As I progressed through my Army career I’d play here and there to keep my skills fresh, and by the end of my first enlistment I knew I was going to get out and pursue my other dream of being a professional golfer.

I think my time on the teams solidified my discipline and drive in trying to make it as a golfer. Golf is a very lonely endeavor and you need to have a ton of self-motivation. That said, I did like the fact that it was something I could do by myself and wouldn’t have to worry about finding someone else to play or practice with. I guess you could say I’m dichotomous in a way: I love being on a team and around others, but there’s definitely a side of me that enjoys being by myself and controlling my own decisions. Although quite different on the surface, there are actually a lot of parallels in the mental discipline it takes to be a Special Operations soldier and a golfer at the highest level. I think that’s part of what I found so intriguing about both.

So, why’d you step away for the time being?

KD: Stepping away from golf remains one of the toughest decisions I’ve ever had to make. I put 9 ½ years of my heart and soul into making that dream a reality, and stepping away really sucked. I was my own financial backer and I was struggling with making enough money to sustain myself. During the months leading up to my decision, I found myself in a seemingly endless playing rut (I developed a case of the driver yips). So I set some pretty harsh criteria that I told myself I had to meet or exceed in order to continue playing. When I arrived at my deadline I hadn’t met that criteria. I could’ve easily ignored my results, but I had to maintain my integrity and keep myself honest. I had to hold myself accountable because no one else was there. I still struggle with my decision every day, wondering if I made the right choice or not. However, I find solace in the fact that I will never have to live with the regret of not trying. I did the best I could with the resources I had. If you can look back at your life and honestly say you did everything within your power to make something happen, then that’s all you can ask of yourself, regardless of the outcome. At the end of the day, I’m batting 0.500 on achieving my lifelong dreams. I can accept that.

How do we bridge the gap between veteran and civilian societies?

KD: It’s like any successful relationship: there has to be compromise. Both civilians and veterans have to come together to ensure a smooth re-integration process back into the civilian world. On the civilian side, you have to realize what you’re getting in a veteran. You’re getting a person with a sense of duty, a tireless work ethic, and an understanding of team dynamics, among other things. I think vets make up about 0.4 or 0.5% of the current population. So realize you’re getting a rare commodity when you hire a veteran, and it’s someone who can provide a perspective that most people cannot. On the flipside, veterans can’t make civilians feel bad when they don’t hire you. You have to show up well to interviews and sell yourself and then prove yourself even more when you do land a job. The worst thing you can do is go into a job or interview or anywhere looking for a hand-out. As a vet, you have to make the effort just like you did in the military. You have to be able to clearly communicate your skills and effectively show people why you’re valuable to their company. There are so many skills that translate from military to civilian life, but often times civilians and vets speak a different “language.” You need to adapt and translate your skills to your prospective employer using their terminology.

What’s one of the biggest stereotypes you see in the veteran community that you’d like to overcome?

KD: There’s this stereotype that is centered on everyone who is a vet is broken and has PTSD. Just because we’ve been in combat and other highly stressful and hazardous situations doesn’t mean we’re broken or that we all automatically have PTSD. Are there unique issues veterans deal with? Sure. And there are a lot of service members who do have legitimate issues, PTSD being one of them. But in my experience the reaction to those combat stressors is normal given the stimulus. I’m not saying to ignore the people who have issues or struggle with certain things. I just wish there was an equal focus on the veterans who are doing good, positive things after their time in service. Those things speak to the resiliency of service members that have seen combat. I know I’m not the first person to mention this, but I think PTG (Posttraumatic Growth) should be the focus for veterans. On the same note, veterans have to take accountability for their actions and not feel sorry for themselves or let outside influences sympathize them into a defeatist mindset. You must always keep growing.

Talk about your relationship with Mission 6 Zero and what you’ve done with them?

KD: I started working with Mission 6 Zero in 2012 with Jason Van Camp. My role has varied throughout the years but the main thing I’ve been involved with is being an operations director, instructor, role player, and teacher for the leadership events that we conduct. I’ve done everything from sitting one-on-one with Tim Tebow and seeing how he handles stress, to leading a fake hostage takedown of our corporate clients. All of the work is centered around leading NFL players or corporate clients through stressful situations and evaluating their leadership characteristics. Through that evaluation, we’re able to give them real world feedback where we can hopefully enhance their leadership skills or the way they cope with stress. These processes were modeled after things we learned during our time in the Special Operations world. These events are unique because we aren’t just sitting in a classroom. We’re doing hands-on, physical events with these guys where we see how they’ll react to certain emotional stressors and how they handle the ethicality of other situations.

What do you think is most effective about Mission 6 Zero’s approach to their events?

KD: Mission 6 Zero’s training model is based on the same model that makes an effective Special Operations team. We use specific scenarios that are designed to elicit physical and mental stress from a person and/or team. Taking guys through these scenarios enhances their mental toughness. That’s one of the performance mechanisms we seek to impart. It doesn’t matter if you’re on an NFL team or a Special Operations team. Those mental pressures will come up and you have to know how you react in when you’re in a stressful situation. Mission 6 Zero is about enabling people to identify and strengthen their responses to those types of situations. Mutual hardships is another powerful mechanism we use to bring teams together and make them more cohesive.

Why do you think veterans should strive to start their own businesses and not necessarily settle for a corporate job?

KD: I don’t think taking a corporate job is necessarily settling. I think veterans have a lot to offer the corporate world in the way of being strong leaders and not being easily phased by things that might stress out others. I see this on a daily basis. Some of the best leaders at my current company are veterans. There’s also a lot to be learned in a corporate environment that can’t be taught elsewhere. That said, though, veterans do tend to have the leadership, discipline, and stress tolerance that are helpful when starting a business. Vets are also generally very task-oriented, which helps get stuff done on a daily basis. It all comes down to knowing what you want to do. If you know you just want to operate a small business, that’s fine. You probably won’t need corporate experience. But if you have aspirations to grow your business to being on the Fortune 500 list, I would say you should definitely seek a job where you will gain exposure to that type of environment. At the end of the day it’s very important to keep an open mind and be a sponge for learning new things. Just because you are a veteran and possess a unique set of skills doesn’t mean you know it all.

Kyle Daniels is the quintessential example of the thinking man's soldier, which is the indelible mark of an elite Special Operations soldier. In an occupation that requires a never ending knowledge base, there are no breaks in education. Daniels has continued that even past his career into his civilian life, and is a wonderful example of that can-do spirit found so commonly in our Special Forces war-fighters. There's no doubt that his approach to life will not only serve as an example to those that follow his route into the SF pipeline, but those reintegrating upon leaving the service. Check out Kyle Daniels and Firebrand Flags on Instagram at @firebrandflags, on Facebook at Firebrand Flags.

Read the original article here.